This Colorado Town Feels Like An Old Western Except There’s Coffee And Killer Views

Ouray, Colorado sits tucked into a box canyon at 7,792 feet, surrounded by the San Juan Mountains in a way that feels almost intentionally cinematic.

From the moment you arrive, it is hard not to slow down, partly because the scenery demands attention and partly because the town itself seems to move at a gentler pace.

Walking down Main Street feels like stepping onto a movie set where saloons and Victorian storefronts line the road, only now they are filled with coffee shops, art galleries, and gear stores instead of gunslingers.

Known as the Switzerland of America, Ouray earns the nickname with towering peaks that rise straight from town, cradling fewer than 900 residents in a setting that feels wildly dramatic for such a small place.

In Colorado, mountain towns often impress, but this one feels especially bold, almost overwhelming in the best way.

Waterfalls tumble down sheer cliff faces, rock formations appear around every corner, and the views are so striking they stop you mid stride without warning.

Simple errands turn into mini adventures because there is always something new pulling your eyes upward.

In Colorado, places like Ouray remind you that beauty does not need to be subtle to be meaningful.

It can be loud, immersive, and completely unforgettable, leaving you grateful that everything takes just a little longer here.

Hot Springs History Runs Deep

Ouray’s relationship with hot springs long predates tourism, beginning with Ute tribes who used the mineral rich waters for centuries before miners arrived in the 1870s. As the town grew, locals formalized that tradition by building the first bathhouse in 1927, setting the foundation for the soaking culture that still defines Ouray today.

The geothermal water rises from deep underground at temperatures reaching roughly 150 degrees before being cooled to levels suitable for bathing, allowing visitors to experience natural heat without discomfort. I spent an evening at Ouray Hot Springs Pool at 1220 Main St, a large and welcoming facility with shallow areas for families and deeper soaking pools where locals unwind after work.

Steam drifts upward into the cool mountain air, creating an almost surreal atmosphere, especially near sunset when surrounding peaks glow pink and orange. The mineral content leaves skin feeling remarkably soft, though a quick shower afterward helps keep the sulfur scent from lingering.

Beyond the main pool, several smaller commercial hot springs operate around town, each offering its own mood and crowd. Together, they make soaking less of an attraction and more of a daily ritual woven into life in the mountains.

Million Dollar Highway Earns Its Name

US Highway 550 between Ouray and Silverton is famously known as the Million Dollar Highway, and the origin of its name depends on who you ask. Some locals say it refers to the enormous cost of construction, others claim the roadbed contains ore rich gravel, and many insist it simply describes the million dollar views that unfold around every bend.

What is beyond debate is that this 25 mile drive demands your full attention. Sheer drop offs run along one side, guardrails disappear for long stretches, and switchbacks feel far tighter when you are actually behind the wheel than they ever appear on a map.

The highway climbs to 11,018 feet at Red Mountain Pass, threading through terrain so rugged that snow can linger well into spring and return early in the fall. I found myself white knuckling the steering wheel through several hairpin turns while my passenger focused entirely on photographing the scenery, which perfectly captured the balance of tension and awe the drive creates.

Abandoned mining structures cling to steep slopes above the road, quiet reminders that people once worked these mountains in brutal conditions year round. In autumn, golden aspens explode against red rock and gray stone, producing colors so intense they hardly seem real and turning an already unforgettable drive into something almost surreal.

Ice Climbing Transforms Winter

Every winter, the city of Ouray deliberately floods the walls of Uncompahgre Gorge to create the world’s first public ice park, turning the narrow canyon into a frozen playground that draws climbers from around the globe. The result is the Ouray Ice Park, which stretches for nearly three miles and features more than two hundred named ice and mixed routes.

These lines range from beginner friendly flows that ease newcomers into the sport to towering vertical pillars that make your palms sweat just watching someone else attempt them. Park staff rely on a sophisticated sprinkler system to build and shape the ice all season long, carefully maintaining routes as temperatures rise and fall.

I took an introductory clinic here and quickly learned how addictive the sport can be. Swinging ice axes into frozen waterfalls feels equal parts terrifying and exhilarating, and the solid thunk of a good placement instantly boosts confidence and curiosity to keep climbing.

Each January, the town hosts the Ouray Ice Festival, filling the streets with professional climbers, gear vendors, competitions, and packed clinics that energize the entire community. Even for visitors who never clip into a rope, standing along the gorge and watching climbers move across glowing blue ice is mesmerizing.

The park turns winter into a spectacle that feels both extreme and welcoming.

Main Street Keeps Its Character

Main Street in Ouray stretches only a few compact blocks, yet those blocks hold enough preserved Victorian architecture to earn the town designation as a National Historic District in 1983. Walking the street feels like moving through a living snapshot of the silver boom era of the 1880s, when saloons, hotels, and mercantile shops supported a rapidly growing mining community.

Many of those original buildings now house coffee shops, restaurants, and small boutiques, but they manage to feel authentic rather than staged, avoiding the polished theme park atmosphere that can creep into historic towns. The Western Hotel still operates at 210 7th Ave, its red brick facade looking much the same as it did when it opened in 1891, while the nearby Beaumont Hotel preserves its 1886 grandeur with modern comforts tucked discreetly behind historic walls.

I stopped for coffee in a shop set inside a former assay office and found myself distracted by the original tin ceiling while locals chatted casually about trail conditions and upcoming weather. The scale of downtown remains human and walkable, with nearly everything you might need just a few minutes away on foot.

No chain stores interrupt the streetscape, giving Ouray a sense of continuity and authenticity that many Colorado mountain towns lost long ago.

Box Canyon Falls Thunders Year-Round

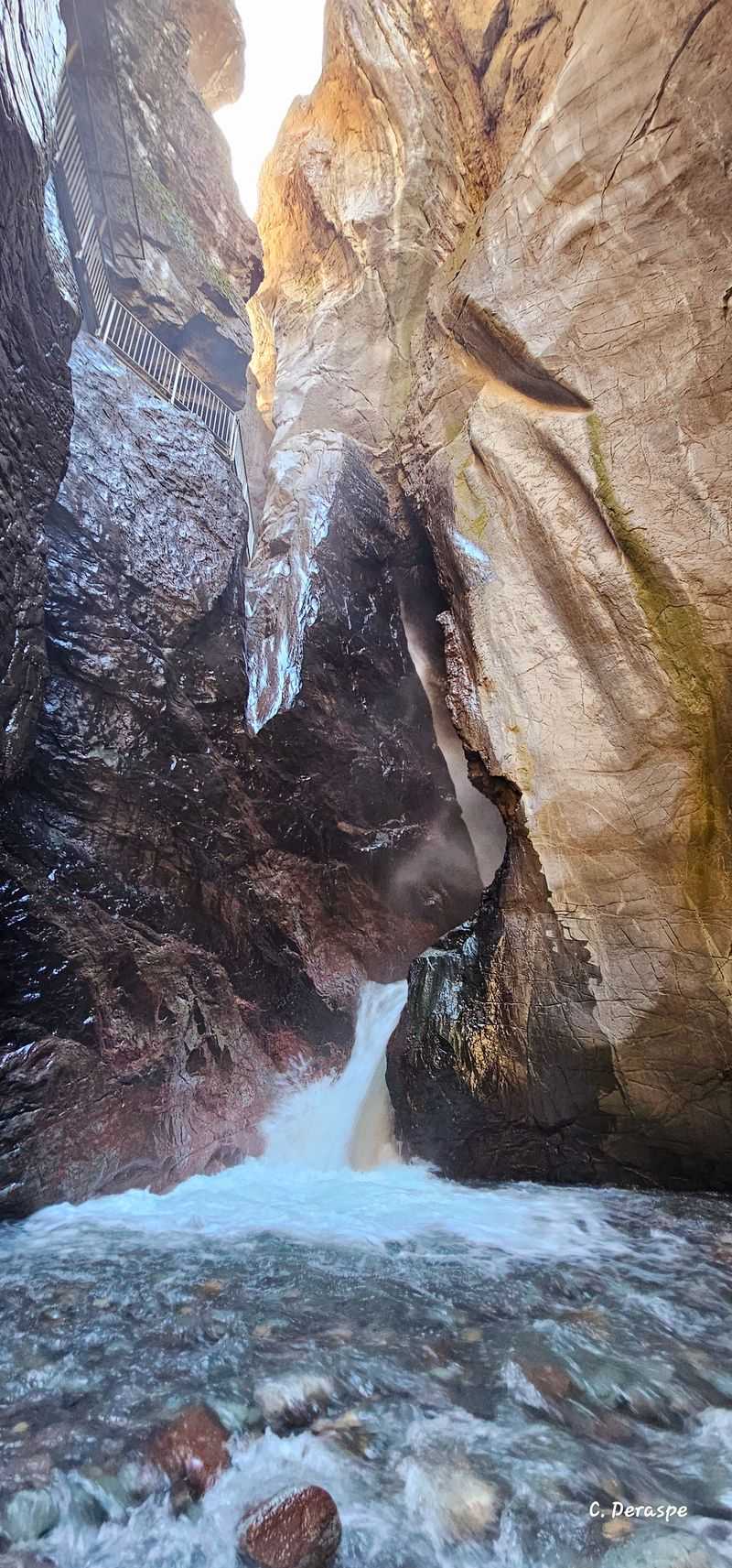

Box Canyon Falls plunges 285 feet through a slot canyon so tight that the sound of rushing water feels almost physical, vibrating through the metal walkway suspended above the churning creek below. The city maintains this dramatic site as a park at the south end of Ouray, charging a modest fee for access to the walkways and viewing platforms that let you look straight into the canyon’s narrow throat.

Canyon Creek has been carving through solid rock here for thousands of years, and standing above it gives a powerful sense of that relentless force. I underestimated the spray on a cool day and wore only a light jacket, quickly discovering how thoroughly the mist can soak you, a mistake longtime locals likely saw coming.

The walkway extends deep into the canyon, bringing you close enough to feel the air pulse with the waterfall’s energy and to spot rainbows forming in the spray when sunlight hits at just the right angle. A tunnel blasted through the rock in 1907 offers another viewpoint, though the constant dampness and echoing roar can feel claustrophobic for some visitors.

Fed by snowmelt and underground springs, the falls run year round, making them a reliable and unforgettable stop in any season.

Jeeping Opens Backcountry Access

The mountains surrounding Ouray hide hundreds of miles of former mining roads that now function as jeep trails, ranging from mellow dirt tracks to rocky routes that demand true four wheel drive and steady nerves. Many of these roads were carved into the mountains during the mining boom and still follow the same improbable lines etched into steep terrain.

Engineer Pass and Imogene Pass both climb above 13,000 feet, linking Ouray with neighboring mountain towns along routes that were engineering marvels in the 1870s and feel borderline unreal by modern standards. I rented a Jeep and chose Yankee Boy Basin, a relatively moderate option that climbs into a broad alpine bowl filled with summer wildflowers and scattered remnants of the old Sneffels Mine.

The drive alternated between smooth dirt and stretches where careful tire placement was needed to navigate rocks the size of basketballs, with occasional pull offs allowing faster vehicles to pass. The exposure and scenery keep your attention fully engaged, even on easier sections.

For visitors who would rather focus on views and wildlife, several local outfitters offer guided jeep tours led by experienced drivers. These high elevation routes are typically buried in snow until July and begin closing again by October, creating a short but spectacular window to explore Ouray’s rugged backcountry.

Small Town Life Persists

Despite waves of tourists that swell the population during peak summer and winter seasons, Ouray remains a real year round community shaped by people who live, work, and raise families in this dramatic mountain setting. Its role as the county seat concentrates government offices and essential services in town, giving Ouray an importance that extends beyond its small footprint.

The local school system serves students from surrounding areas, with buses navigating mountain passes that occasionally close when weather turns severe. While waiting at the post office, I spoke with a woman whose family has lived in Ouray for five generations, shifting between mining, ranching, and tourism as the local economy changed over time.

That kind of continuity feels rare and speaks to the resilience of the place. With a population of just 898 recorded in the 2020 census, Ouray ranks among Colorado’s smallest incorporated municipalities, fostering a tight knit atmosphere where faces quickly become familiar and conversations carry shared context.

Housing costs and limited inventory make relocating difficult, and many workers commute from more affordable towns down the valley to keep the community running. Civic engagement runs high, with local government meetings drawing strong attendance because decisions here affect daily life in immediate and personal ways.

It is a town where participation matters and neighbors genuinely know one another.