Abandoned Towns In Michigan That Nature Is Gradually Reclaiming

There is a certain frequency you only find in the pockets of Michigan where the machines finally stopped humming and the maples moved back in to claim the silence. Walking these forgotten corners feels less like a hike and more like a conversation with a patient ghost.

I’ve found myself standing among brick and iron softened by a decade of moss, realizing these ruins are slow-motion stories written in cedar needles and the heavy, blurring weight of lake fog.

If you slow your heartbeat and look closely, the landscape begins to reveal its secrets: a boardwalk that leads to nowhere, or the jagged, skeletal outline of a schoolhouse surrenderd to the dune grass.

Uncover the hauntingly beautiful history of Michigan’s most evocative ghost towns and abandoned heritage sites. The past is still very much breathing under the damp leaves, waiting for someone with a light step and a curious soul to listen.

Singapore, Near Saugatuck And Douglas

Wind sounds like a slow broom across the dunes where Singapore once stood, and the sand keeps moving. Boardwalks from nearby Saugatuck lead toward ever shifting ridges, with hints of old pilings appearing after storms. The lake breathes cool air that smells faintly of pine and wet quartz.

Lumbering boomed here in the 1830s, and overharvested forests fed Chicago’s growth. Sand encroachment and economic decline finished the town by the late 19th century. Guides in Saugatuck Dune Rides tell pieces of the story while tires hum over soft hills.

Visit on a clear morning for best visibility, and tread lightly on protected dunes. Read shoreline conditions, respect closures, and let the wind reveal what it chooses.

Fayette Historic Townsite, Near Garden Peninsula

Cliffs rise like bright knuckles above Snail Shell Harbor, and the water looks impossibly teal against weathered limestone. The empty furnaces hold a quiet tone that feels respectful rather than eerie. Waves tap the dock posts, keeping time for gulls.

From 1867 to 1891 this company town smelted pig iron using local limestone and charcoal. When the charcoal era ended, so did Fayette. Conservation crews stabilized foundations and reconstructed boardwalks, turning decline into an open air lesson.

Pick up a map at the visitor center and walk the town loop, reading the iron-making steps in order. Late afternoon light is beautiful for photos. Stay on paths, and watch for poison ivy fringing the margins.

Pere Cheney, Near Grayling

White sand soil swallows footprints quickly in the clearing where Pere Cheney’s cemetery rests under thin pines. The air smells medicinal, as if the forest keeps old tonics on a shelf. A few stones lean, and lichen writes over names.

Once a late 19th century lumber settlement on the Michigan Central Railroad, it dwindled after fires and disease outbreaks. There is more rumor than record now, but county archives confirm the basics. The village site returned to jack pine and low blueberry.

Access by sandy two-tracks south of Grayling, best with high clearance. Keep visits quiet, pack out everything, and avoid night trespass myths. Daylight reveals enough: the hush, the resin, the thin light.

Deward, Near Frederic

Jack pines knit a patchwork where houses once stood, and the ground feels springy with needles. A two-track slides past stone footings like the town’s spine remembering its shape. Woodpeckers provide the only percussion.

Deward grew around a massive mill built by David Ward in the 1890s. When the timber was cut and the mill closed, residents drifted away. Today the Deward Tract is managed forest, with history summarized on small roadside plaques.

Arrive with a reliable map or offline GPS, because cell service wobbles. Look for foundation outlines near trail junctions, and watch for ORV traffic. In dry weather, bring water and a bandana for the dust that lingers after trucks.

Port Oneida, Near Glen Arbor

Mist lifts off hayfields and reveals barns with paint rubbed thin as corduroy. Birds stitch the hedgerows while grasshoppers click underfoot. The quiet here is working quiet, not spooky, and it suits the slow curve of the hills.

Port Oneida was a community of subsistence and market farms dating from the mid 19th century. As agriculture shifted, families left, and the National Park Service preserved the landscape as the Port Oneida Rural Historic District. Volunteers stabilize roofs and sills without overpolishing.

Start at the Olsen Farm for context, then loop the gravel lanes by bike. Respect closures during nesting season, and step softly around old foundations. Late August brings warm light and monarchs drifting over fences.

Aral, Near Empire

Otter Creek whispers through alders where mill wheels once chattered, and the dunes crouch just beyond the trees. You notice squared-off hollows in the ground like missing teeth. The air tastes mildly tannic from the creek.

Aral thrived briefly in the late 1800s as a sawmill settlement feeding Great Lakes shipping. When logs and markets shifted, the town thinned to nothing, leaving foundations and stories captured by park interpreters. Nature braided itself back into the grid.

Trailheads south of Empire lead to signed stops explaining mill life and transport. Wear waterproof boots in spring, and expect mosquitoes. Keep to established paths to protect fragile wetland edges, and linger where the creek slows.

North Manitou Island Village, On North Manitou Island

Waves slap the old dock pilings like a metronome, and beach grass combs the wind into tidy lines. The village sits back from the shore with weathered sheds and a schoolhouse frame. Everything smells of cedar and lake salt.

North Manitou’s village supported farming, logging, and steamship traffic into the early 20th century. After depopulation, the National Park Service managed the island as designated wilderness, preserving select structures. Rangers monitor stabilization rather than full restoration.

Reach it by ferry from Leland, permits required for overnight camping. Water is precious, so treat sources and pack carefully. I like dawn loops around the village before heading inland, when footprints are fresh and gulls patrol.

Crescent, On North Manitou Island

Old apple trees lean into the meadow at Crescent, their fruit small and tart, still dropping with a neat thud. Aspen saplings fence the clearings with pale trunks. A collapsed barn perfumes the grass with sun-warmed wood.

Crescent was a farming district tied to the island’s broader agricultural experiment. As markets shifted and population drained, buildings fell and orchards went feral. Park managers document sites, allowing slow natural reclamation.

Navigate by topo map from the island village, keeping an eye on ticks in tall grass. Bring a small notebook to sketch site layouts before they’re swallowed. Late September is generous with cool air, bright asters, and that crisp, ferry-home horizon.

Central Mine, Near Eagle Harbor

Granite tailings crunch underfoot like broken plates, and the church bell tower watches the slope. Weathered clapboard houses sit with curtains drawn just so. Lake Superior air scrubs everything clean.

Central Mine produced rich copper in the 19th century, then tapered off and closed by 1898. Descendants return annually for a homecoming service at the Methodist Church, a tradition linking memory and place. Volunteers carefully conserve structures, leaving tool marks visible.

Begin at the Keweenaw National Historical Park signs and follow the self-guided route. Wear sturdy shoes for uneven ground, and avoid open shafts. Museum hours vary by season, so check ahead. Evening light gilds the ridge and quiets the chipmunks.

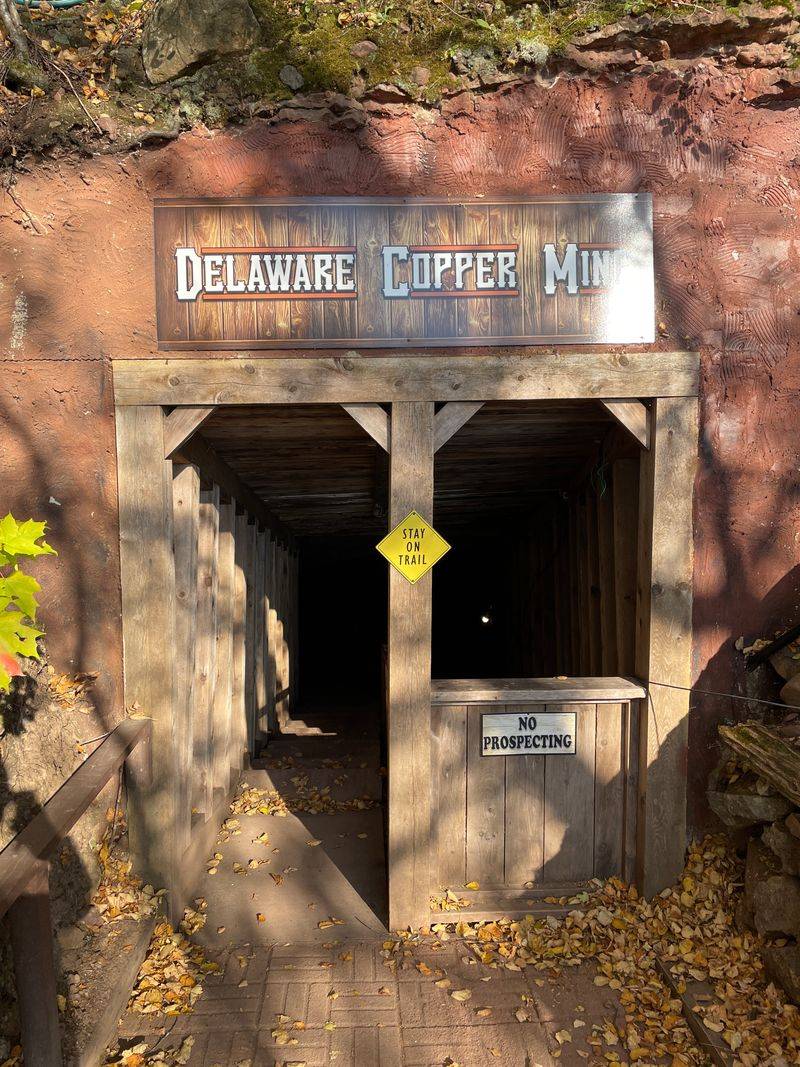

Delaware, Near Copper Harbor

Cold air pours from the mine entrance like a steady exhale, even in July. Ferns fringe the rock piles in bright green applause. Rusted pulleys and timbers frame the headworks against changeable Superior skies.

Delaware boomed with underground copper mining beginning in the 1840s. When ore grades fell, the town thinned, leaving a few buildings and miles of drifts below. Caretakers maintain safe tour sections and surface artifacts for context.

Take the guided underground tour for orientation and a hardhat perspective. It is chilly, so pack a layer and good shoes. Stay within bounded areas, and give yourself time on the surface loop. The silence after the tour feels earned.

Clifton, Near Eagle Harbor

Birch trunks shine like matchsticks among sandstone blocks at Clifton, and the forest is busy with small sounds. You can trace street lines by how the understory hesitates. A raven’s rattle carries down the old grade.

Clifton supported the Cliff Mine in the mid 19th century, once one of the peninsula’s most productive copper sites. When operations shifted, residents dispersed, and structures followed. Today, signage and careful fencing emphasize preservation and safety.

Park at the marked pullouts along Cliff Drive and explore short paths to foundations. Resist the urge to hop fences near shafts. Bring bug spray in June, and patience for reading the ground like a faded ledger.

Freda, Near Houghton

Waves rake the black stamp sands at Freda, leaving crescent swashes that shine like graphite. Concrete shells of the mill guard the shore, their windows mapping squares of sky. Gulls argue over the pier stubs.

The Champion Mill once pounded copper-bearing rock here, and its tailings reshaped the beach. When the mill closed mid 20th century, the town’s purpose faded. Remnants now draw photographers and Great Lakes historians, with ongoing discussions about environmental legacy.

Access via Freda Road west of Houghton, with limited services. Watch footing on sharp ruins, and respect private property nearby. Sunset paints Superior like poured copper, but the wind turns fast, so bring layers and a headlamp.

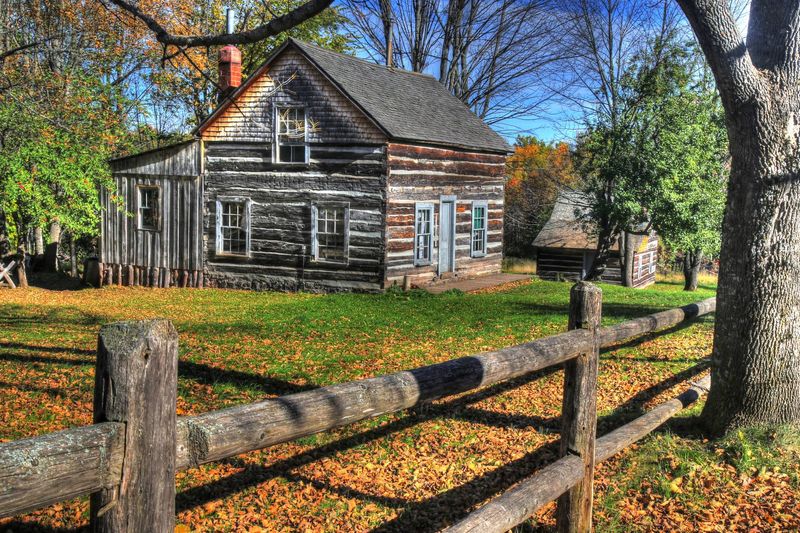

Old Victoria, Near Rockland

Smoke curls from a demonstration stove on special days, and the cabins smell of resin and soap. Ax-hewn logs fit together with a logic you can feel through the chink lines. The hillside listens while visitors shuffle between doorways.

Old Victoria housed miners who worked nearby copper lodes in the late 1800s. Volunteers restored several cabins using period techniques, keeping scars and tool marks honest. It is a preservation story that favors use over display.

Check the Old Victoria Restoration Society schedule for open hours and events. Bring cash for a modest tour donation and a baked good if you are lucky. I always linger on the porch steps, watching wind bend the grass in long waves.