15 Unforgettable Arizona Day Trips You Can Easily Take In 2026

Arizona keeps surprising me every time I plan what I think will be a simple day trip. One minute I’m standing at the edge of a canyon that makes my jaw drop, and the next I’m crawling through caverns that took millions of years to form.

The desert landscape here shifts between painted rocks, towering saguaros, ancient ruins, and geological wonders that feel like they belong on another planet.

I’ve spent years exploring this state, and I still find new reasons to wake up early, pack a cooler, and hit the road for another adventure that’ll be back home by dinner.

Arizona day trips never stay simple, because every quick drive turns into a canyon view, a cave crawl, and a desert wow moment you end up talking about all week.

1. Grand Canyon South Rim

Standing at Mather Point for the first time, I completely forgot what I was going to say mid-sentence.

Grand Canyon South Rim sits in northern Arizona near the town of Grand Canyon Village, about 80 miles north of Flagstaff, and the view from every overlook still catches me off guard no matter how many times I visit.

The South Rim stays open year-round, which means I can watch sunrise paint the canyon walls in shades of copper and gold even during winter months when snow dusts the rim.

Bright Angel Trail offers a chance to hike below the rim, though I learned quickly that going down is the easy part and my legs reminded me of that fact for days afterward.

Desert View Watchtower provides a different perspective, with stone architecture that blends into the canyon edge and windows that frame the Colorado River far below.

Every visit teaches me something new about geology, patience, or just how small I really am in the grand scheme of things.

I keep returning because no photograph ever captures what standing on that rim actually feels like.

2. Antelope Canyon

Light beams cutting through narrow sandstone walls turned my skepticism about “overhyped” tourist spots into pure wonder.

Antelope Canyon lies near Page, Arizona, on Navajo Nation land, and guided tours remain the only way to access these slot canyons that wind through rock formations sculpted by flash floods over thousands of years.

Upper Antelope Canyon, known as “The Crack,” lets more light filter down, creating those famous beam shots that photographers wait hours to capture during midday summer months.

Lower Antelope Canyon requires climbing a few ladders and squeezing through tighter passages, but the swirling rock patterns and quieter atmosphere made it my personal favorite of the two sections.

I visited in March and still saw plenty of beautiful light playing across the curved walls, even without the dramatic summer beams that fill social media feeds.

Navajo guides share stories about the canyon’s formation and cultural significance, adding context that turns a pretty walk into something more meaningful.

Booking ahead is essential because slots fill up weeks in advance during peak season.

3. Horseshoe Bend

My palms got sweaty the first time I walked to the edge and looked straight down at the Colorado River making its famous curve.

Horseshoe Bend sits just outside Page, Arizona, about 4 miles south of town, where a short three-quarter-mile walk from the parking area leads to one of the most photographed river bends in the American Southwest.

The overlook has no guardrails along most of the rim, which means I stayed a respectful distance back while braver visitors dangled their legs over the thousand-foot drop.

Sunrise and sunset paint the canyon walls in constantly shifting colors, though midday light reveals the true turquoise tint of the river below.

I recommend bringing plenty of water because that walk back to the parking lot feels twice as long when the Arizona sun is beating down on the exposed trail.

The view has become so popular that the National Park Service installed a parking lot and bathroom facilities to handle the crowds that show up year-round.

Every angle offers a slightly different perspective on how water carved such a perfect bend through solid rock.

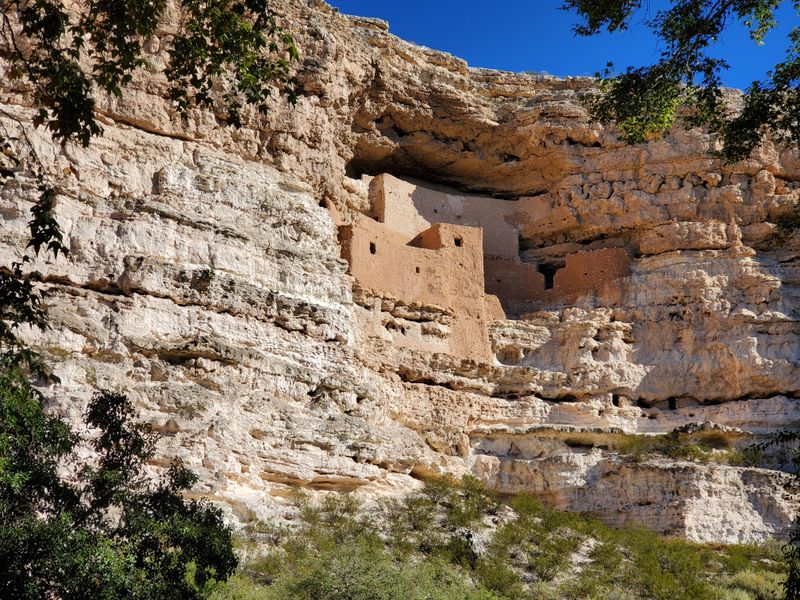

4. Montezuma Castle National Monument

Craning my neck to study the cliff dwelling tucked into the limestone wall, I tried imagining hauling building materials up there without modern tools.

Montezuma Castle National Monument sits near Camp Verde in central Arizona’s Verde Valley, about 90 miles north of Phoenix, where Sinagua people constructed this five-story dwelling into a cliff recess around 1100 CE.

The monument has nothing to do with Aztec emperor Montezuma, but early settlers made that incorrect assumption and the name stuck despite the 600-year timeline mismatch.

Visitors can’t climb up to the dwelling anymore, which protects the fragile structure but also means I spent my time studying the architecture from the paved trail below.

Twenty rooms housed about 50 people in this vertical apartment building that stayed cool in summer and warm in winter thanks to its protected cliff position.

The short loop trail takes maybe 30 minutes to walk, making this an easy stop when driving between Phoenix and Flagstaff.

I left with more questions than answers about daily life in a home suspended 100 feet above the valley floor.

5. Montezuma Well

A natural limestone sinkhole pumping 1.5 million gallons of water daily into the desert sounds like something I’d make up, but Montezuma Well proves otherwise.

This detached unit of Montezuma Castle National Monument sits about 11 miles northeast of the main castle site, where a collapsed underground cavern created a pool that measures 368 feet across and 55 feet deep.

Ancient Sinagua and Hohokam people built irrigation ditches that still channel water from the well to the surrounding land, showing engineering skills that sustained agriculture in an arid climate.

I walked the rim trail and spotted cliff dwellings tucked into the walls above the water, smaller than the main castle but equally impressive given their age and construction challenges.

The water contains high levels of carbon dioxide and arsenic, which means no fish live in the well, though unique aquatic species found nowhere else on Earth thrive in these specific conditions.

A short trail leads down to the outlet where water flows through the original prehistoric irrigation ditch.

This spot gets fewer visitors than the main castle, which made my morning visit feel peaceful and unhurried.

6. Tonto Natural Bridge State Park

Walking beneath what might be the world’s largest travertine bridge made me feel like I’d stumbled into a secret Arizona keeps hidden in the mountains.

Tonto Natural Bridge State Park sits near Payson in central Arizona’s Mogollon Rim country, about 95 miles northeast of Phoenix, where a 183-foot-tall bridge spans a 150-foot tunnel carved by Pine Creek over thousands of years.

The park offers four trails that provide different perspectives, from viewing the bridge from above to scrambling down rocky paths to stand in the creek below the massive arch.

I took the Pine Creek Trail down to the bottom, which required careful footing on steep sections but rewarded me with a cool, shaded spot where water drips constantly from the bridge ceiling.

Travertine deposits continue forming today, which means this bridge grows slightly thicker each year as minerals precipitate from the flowing water.

Summer weekends bring crowds, but visiting on a weekday morning gave me plenty of space to explore and photograph without dodging other hikers.

The park’s remote location means this natural wonder stays off most tourist itineraries despite being absolutely worth the drive.

7. Saguaro National Park

Forests don’t have to contain trees, as I learned driving through thousands of saguaros standing like sentries across the Sonoran Desert.

Saguaro National Park protects two separate districts on the east and west sides of Tucson, Arizona, where these iconic cacti grow naturally only in this specific region of the Southwest.

The Rincon Mountain District (east) offers more hiking trails and backcountry options, while the Tucson Mountain District (west) provides better sunset views and easier access from downtown Tucson.

Saguaros grow incredibly slowly, taking about 70 years to reach just six feet tall and another 25 years before sprouting their first arm.

I visited in late April when the creamy white blossoms crowned the tallest cacti, attracting bats, bees, and birds that pollinate the flowers and spread seeds.

The Valley View Overlook Trail in the west district gave me panoramic views across the cactus forest without requiring a strenuous hike.

These giants can live 150 to 200 years and weigh several tons when fully hydrated, making them true survivors of the harsh desert climate.

8. Sabino Canyon Recreation Area

Water flowing year-round through a desert canyon creates an oasis that feels almost impossible given the surrounding Tucson landscape.

Sabino Canyon Recreation Area sits in the Santa Catalina Mountains on Tucson’s northeast side, where Sabino Creek carved a canyon that offers hiking, swimming holes, and a tram ride through scenery that shifts from desert scrub to riparian forest.

The tram runs regularly throughout the day, stopping at nine points where visitors can hop off to explore trails or creek access spots before catching a later tram back down.

I hiked instead of riding, which let me set my own pace and stop wherever the light looked good for photos or the water looked inviting for cooling off.

Seven natural stone bridges cross the creek along the main road, each one a perfect spot for watching water flow over smooth rocks.

Winter and spring bring the highest water levels, while summer monsoons can temporarily close the canyon when flash floods roar through.

The area gets packed on weekends, so I started early to claim a quiet spot along the creek before the crowds arrived.

9. Kartchner Caverns State Park

Discovering that Arizona hides a massive living cave system beneath the desert surface completely changed what I thought I knew about the state’s geology.

Kartchner Caverns State Park sits near Benson in southeastern Arizona, about 50 miles east of Tucson, where two amateur cavers found the entrance in 1974 but kept it secret for 14 years to protect the pristine formations.

The cave remains a living system with 99 percent humidity that allows formations to continue growing, which means strict protocols control temperature, moisture, and visitor impact.

Two different tours explore separate sections: the Rotunda/Throne Room tour available year-round, and the Big Room tour offered when bats aren’t roosting there from mid-October through mid-April.

I took the Big Room tour and stood beneath Kubla Khan, a 58-foot column that ranks among the tallest in the world still actively forming.

The caverns maintain a constant 68 degrees, making them comfortable any time of year, though the high humidity means my glasses fogged up immediately upon entering.

Reservations are essential because tours sell out weeks ahead during peak seasons.

10. Petrified Forest National Park

Trees turned to stone and scattered across rainbow-colored badlands sound like fantasy, but Petrified Forest National Park makes it real and accessible.

The park sits in northeastern Arizona along Interstate 40 between Holbrook and the New Mexico border, where ancient logs from 225 million years ago fossilized into crystalline quartz that preserved the original wood structure.

A 28-mile scenic road connects the north and south entrances, with pullouts and short trails leading to concentrations of petrified wood and painted desert vistas.

I spent most of my time at Crystal Forest and Giant Logs trails, where massive petrified trunks lie scattered like a giant’s abandoned lumber yard, some still showing bark texture and tree rings despite being solid stone.

The colors come from different minerals that replaced the organic material: iron creates reds and oranges, manganese produces purples and blues, while carbon adds blacks.

Blue Mesa offers a 3.5-mile loop through blue and purple badlands that look more like an alien planet than Arizona.

Taking any petrified wood is illegal, but the gift shop sells legally collected pieces if I wanted a souvenir.

11. Painted Desert Visitor Center

Starting my Petrified Forest visit at the Painted Desert Visitor Center gave me context that made everything I saw afterward more meaningful.

The visitor center sits at the north entrance of Petrified Forest National Park off Interstate 40, where exhibits explain how ancient trees became stone and why the surrounding badlands display such vivid colors.

Rangers lead programs throughout the day, answering questions about geology, paleontology, and the Triassic period when this area was a tropical forest rather than high desert.

The bookstore carries field guides that helped me identify different types of petrified wood and understand the fossilization process that preserved cellular detail in solid quartz.

Large windows frame views of the Painted Desert stretching north, giving me a preview of the colorful landscape I’d be driving through on the scenic road.

I grabbed a park map and asked about current trail conditions, which saved me from hiking to areas temporarily closed for restoration.

The center also houses restrooms and water fountains, important resources before heading into the park where services are limited.

Spending 30 minutes here enhanced my entire park experience.

12. Meteor Crater

A hole nearly a mile wide and 550 feet deep punched into the Arizona desert by a speeding space rock makes abstract concepts like cosmic impacts suddenly very concrete.

Meteor Crater sits on private land about 40 miles east of Flagstaff near Winslow, where a nickel-iron meteorite struck roughly 50,000 years ago with explosive force equivalent to 10 megatons of TNT.

The crater remains so well preserved because the dry climate limits erosion, making it one of Earth’s best examples of a simple impact crater and a training site for Apollo astronauts.

I walked the rim trail, which offers different perspectives on the crater’s size and the violence of the impact that vaporized most of the meteorite instantly.

The visitor center displays a 1,400-pound meteorite fragment found nearby, one of the few pieces that survived the impact explosion.

Interactive exhibits explain impact physics, crater formation, and ongoing research that uses this site to understand similar features on other planets.

The admission price is steep compared to national parks, but the privately funded preservation and excellent educational programs justify the cost.

I left with renewed respect for the cosmic lottery that keeps most space rocks away from populated areas.

13. Chiricahua National Monument

Rock formations balanced in ways that seem to defy physics turned my drive through southeastern Arizona into a detour I’ll never regret taking.

Chiricahua National Monument sits in the Chiricahua Mountains about 120 miles southeast of Tucson, where volcanic eruptions 27 million years ago created the rhyolite rock that erosion sculpted into pinnacles, balanced rocks, and hoodoos.

The scenic drive climbs from the visitor center to Massai Point, offering pullouts where I could photograph formations with names like Duck on a Rock and Punch and Judy.

Echo Canyon Trail became my favorite hike, winding between towering rock columns in a landscape that feels more like fantasy than geology.

The monument’s remote location means fewer visitors than more famous Arizona parks, which gave me plenty of solitude on trails that showcase nature’s architectural creativity.

Apache leader Geronimo used these mountains as a stronghold, taking advantage of the maze-like terrain and reliable water sources.

I visited in October when fall colors highlighted the transition zone between desert and forest ecosystems that meet in these mountains.

The two-hour drive from Tucson feels worth it for landscapes this unusual.

14. Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

Cacti growing in clusters of vertical pipes gave me a landscape that felt distinctly different from anywhere else in Arizona I’d explored.

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument sits along the Mexican border in southwestern Arizona near Ajo, where these rare cacti reach the northern limit of their range in the Sonoran Desert.

The monument protects the only place in the United States where organ pipe cacti grow wild, along with 27 other cactus species that thrive in this harsh but biologically rich environment.

I drove the 21-mile Ajo Mountain Drive, a graded dirt road that loops through the best organ pipe habitat while offering mountain views and wildlife spotting opportunities.

These cacti grow slowly, taking 150 years to reach full height, with multiple arms rising from a common base rather than branching from a central trunk like saguaros.

The monument’s remote location and summer heat mean spring months bring the most pleasant weather and the bonus of desert wildflower blooms.

I filled my gas tank in Ajo before visiting because services are limited and the nearest town sits 35 miles from the visitor center.

This remains one of Arizona’s least visited national monuments despite offering unique desert landscapes.

15. Canyon De Chelly National Monument

Red sandstone walls rising 1,000 feet above a canyon floor where Navajo families still farm and herd sheep created layers of history I could see and touch.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument sits in northeastern Arizona near Chinle on Navajo Nation land, where two main canyons preserve Ancestral Puebloan ruins and continue supporting modern Navajo life.

Three rim drives offer spectacular overlooks of the canyon, including Spider Rock, an 800-foot sandstone spire that features prominently in Navajo stories and stands as the monument’s most photographed feature.

Visitors can only enter the canyon bottom with authorized Navajo guides, which protects both the archaeological sites and the privacy of families living and working in the canyon today.

I joined a guided tour that stopped at White House Ruins, where an 80-room pueblo sits in a cliff alcove above structures built on the canyon floor.

The guide shared stories about the canyon’s significance to Navajo people, adding cultural context that made the ruins more than just old buildings.

This monument offers a rare chance to see how ancient and contemporary cultures share the same landscape across centuries.