This Amazing Ohio Museum Showcases The Work Of One Genius Woodcarver

I’ve visited a lot of museums across the country, but nothing quite prepared me for what I found tucked away in Dover, Ohio. The craftsmanship on display here isn’t just impressive, it’s almost impossible to believe one person created it all by hand.

Ernest “Mooney” Warther spent his lifetime transforming wood, ivory, and bone into intricate steam locomotives and moving mechanical displays that still leave visitors speechless today.

His story is one of dedication, self-taught genius, and a love for his craft that turned a simple hobby into a world-renowned collection.

What makes this place truly special isn’t just the carvings themselves, but the way they tell the story of American ingenuity and the steam age through the eyes of a man who never let his limited formal education hold him back from achieving greatness.

A Self-Taught Master’s Journey

Ernest Warther dropped out of school after second grade, but that didn’t stop him from becoming one of history’s most remarkable woodcarvers. Born in 1885, he started working at a steel mill as a young boy to help support his family.

During his breaks at the mill, he’d carve small items from scrap wood using a pocketknife. What began as a simple pastime evolved into an extraordinary talent that would eventually earn him recognition from museums and collectors worldwide.

The museum (Ernest Warther Museum & Gardens) at 331 Karl Ave, Dover, OH 44622, United States now houses his life’s work, showcasing how determination and natural ability can overcome any obstacle. His carvings demonstrate mathematical precision that engineers still marvel at today.

Warther never used power tools, relying entirely on hand-carved implements he made himself. Each piece took months or even years to complete, with some containing thousands of individual moving parts that function perfectly without glue or metal fasteners.

The Steam Engine Collection

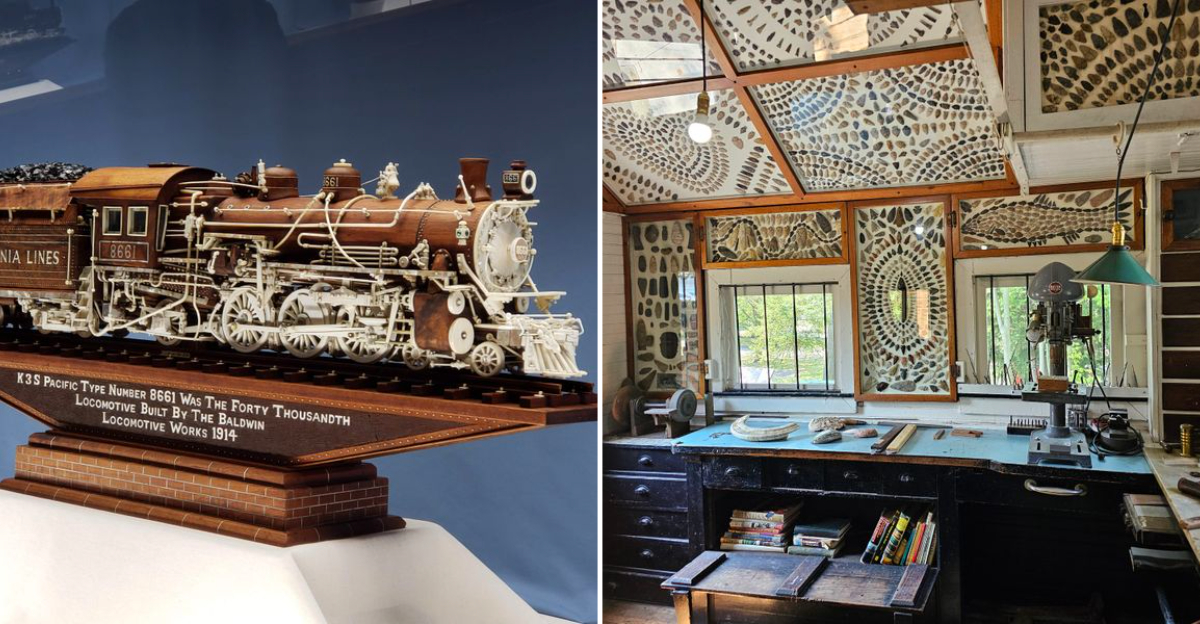

Walking through the main gallery, I found myself face to face with the most detailed wooden locomotives I’ve ever seen. Warther carved the complete history of the steam engine, from its earliest beginnings to the powerful machines that transformed America.

Each locomotive features working wheels, pistons, and gears that move exactly as the real engines did. The level of detail is staggering, with some models containing over 10,000 individual pieces, all hand-carved and fitted together with incredible precision.

He used walnut, ivory, ebony, and even beef bone to create contrasting colors and textures. The materials were chosen not just for aesthetics but for their carving properties and durability.

What amazed me most was learning that Warther worked without blueprints or plans. He studied photographs and descriptions of actual trains, then carved from memory and imagination.

The mechanical accuracy is so perfect that railroad historians use his models as reference materials.

Frieda’s Button Collection

While Ernest carved trains, his wife Frieda collected buttons, and her collection is just as impressive in its own right. The Button House displays over 73,000 buttons she gathered throughout her lifetime, each one carefully preserved and arranged.

Frieda started collecting as a young girl and never stopped. The buttons span centuries and come from all over the world, representing different materials, styles, and historical periods.

Some are made from precious materials like mother-of-pearl and jade, while others are simple utilitarian fasteners from everyday clothing. The collection tells its own story about fashion, manufacturing, and social history across generations.

I spent more time here than I expected, discovering buttons from military uniforms, fancy Victorian garments, and even buttons that once belonged to notable historical figures.

The sheer variety kept me engaged, and the docent shared fascinating stories about how different buttons were made and used throughout history.

Hand-Carved Pliers That Work

One of Warther’s most famous creations wasn’t a train at all, but a pair of fully functional pliers carved from a single piece of wood. These weren’t decorative, they actually worked, with moving jaws that opened and closed smoothly.

Warther gave these pliers away to schoolchildren who visited his workshop, carving them in just minutes while telling stories. Thousands of people across Ohio and beyond still treasure the pliers they received from him as children.

The museum displays several examples, and I couldn’t stop examining how he achieved the moving joint without any glue, nails, or separate pieces. The entire tool, including the pivot point, came from one continuous block of wood.

This simple creation demonstrates his understanding of wood grain, mechanics, and carving technique better than almost anything else in the collection. It’s a reminder that true genius often shows itself in the simplest forms, not just the most elaborate displays.

The Warther Family Home

The tour includes a walk through the actual home where Ernest and Frieda raised their family. The house remains much as it was when they lived there, offering a genuine glimpse into their daily life.

You can see Ernest’s original workshop, where he spent countless hours perfecting his craft. The space is modest, with simple tools and a workbench worn smooth from decades of use.

What struck me most was how normal everything felt. This wasn’t a mansion or an artist’s fancy studio, just a regular family home where extraordinary things happened because of dedication and passion.

Frieda’s kitchen still contains her cooking implements and the family’s everyday dishes. The couple lived frugally despite opportunities to sell carvings for large sums, preferring to keep the collection together for public education.

Their children grew up surrounded by creativity and craftsmanship, and several family members still run the museum today, maintaining the legacy with obvious pride and care.

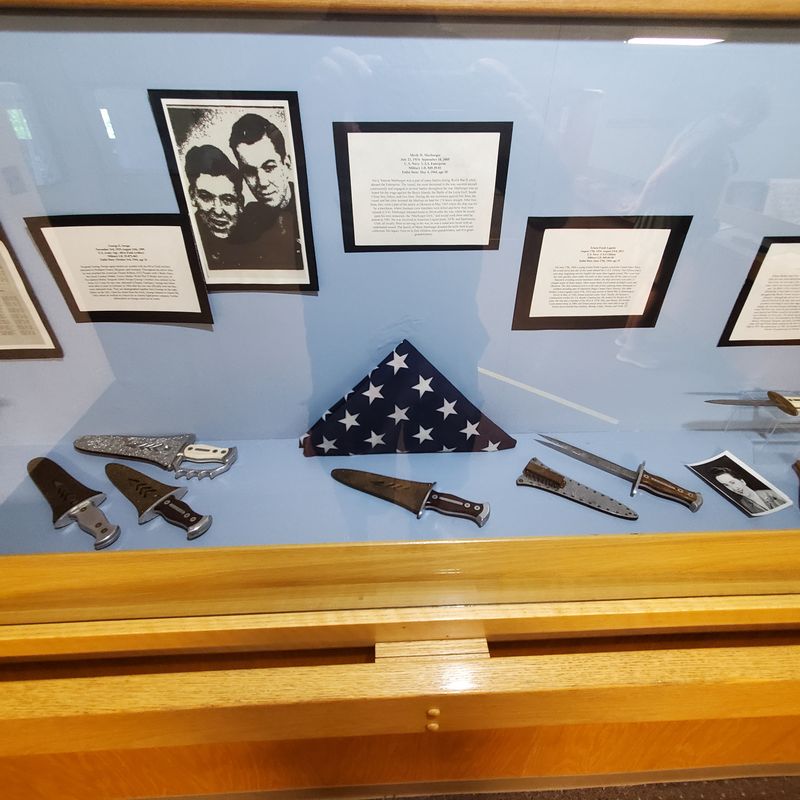

The Knife Factory Legacy

Next door to the museum, the family still operates a cutlery business that Ernest began developing in the early 1900s. The knives are handcrafted using techniques he developed, and they’re known for exceptional quality and sharpness.

During World War II, Warther put aside his peaceful nature to craft commando daggers for soldiers. He became known locally as the “smallest defense plant in the nation,” crafting high-quality fighting knives by hand for the troops.

Today’s production focuses on kitchen knives, carving sets, and specialty blades. I watched craftsmen grinding and sharpening blades the traditional way, using methods that haven’t changed much in decades.

The factory showroom offers knives for purchase, and many visitors leave with a set as a practical memento of their visit. The quality is outstanding, with warranties that last for generations, reflecting the family’s commitment to craftsmanship.

It’s satisfying to see how the Warther dedication to quality continues beyond the museum walls into a living, working business.

The Gardens And Grounds

Between the museum buildings, beautifully maintained gardens provide a peaceful space for reflection. Frieda designed and tended these gardens herself, creating a colorful outdoor gallery that changes with the seasons.

I visited in late spring when everything was blooming, and the combination of flowers, trees, and carefully placed paths made for a serene experience. The gardens aren’t huge, but they’re thoughtfully arranged to complement the buildings.

Several benches offer spots to rest and think about what you’ve seen inside. The grounds feel like an extension of the museum itself, showing another side of the family’s creative spirit.

In winter, the gardens host a Christmas tree festival that draws visitors from across the region. Decorated trees fill the spaces, and admission proceeds go to charity, continuing the Warther tradition of community service.

Even if you’re not typically a garden person, the outdoor spaces add to the overall experience and give you time to process the remarkable craftsmanship you’ve witnessed inside.

Planning Your Visit

The museum is typically open seven days a week, with regular hours of 9 AM to 5 PM from March through December and 10 AM to 4 PM in January and February, though holiday closures mean it’s always wise to confirm current hours before you go.

Admission is reasonable at around twenty dollars for adults, with discounts available for seniors, veterans, and AAA members.

I highly recommend taking the guided tour rather than exploring on your own. The docents, many of whom are family members, share stories and details you’d never get from just reading the displays.

Plan to spend at least two hours if you want to see everything properly. The main museum, Button House, family home, and gardens each deserve attention, and rushing through would mean missing important details.

The museum is located in Dover, about 45 minutes south of Akron in eastern Ohio. The area is part of Amish Country, so you can easily combine your visit with other regional attractions.

Photography is allowed in most areas, though flash might be restricted near delicate carvings. The gift shop offers books about Warther’s life and smaller carved items that make meaningful souvenirs of a truly unique experience.