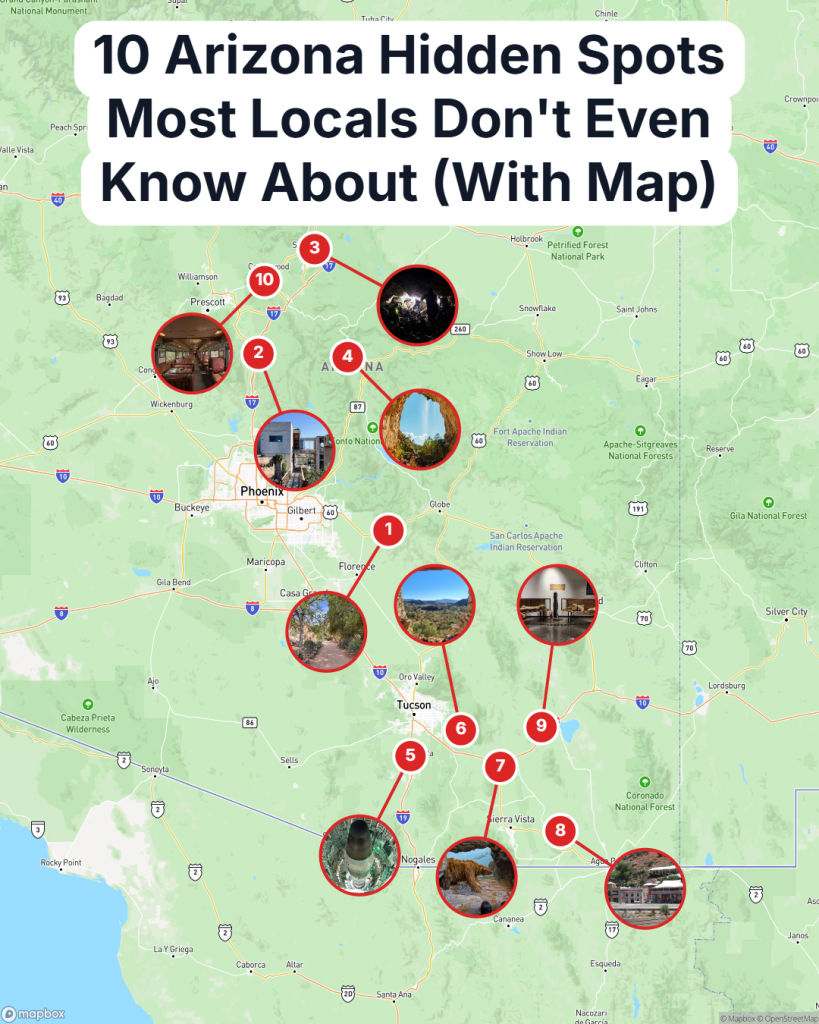

10 Arizona Hidden Spots Most Locals Don’t Even Know About (With Map)

Most people think they know Arizona pretty well after visiting the Grand Canyon or hiking Camelback Mountain. But what if the best way to experience this state isn’t by visiting the postcard spots, but by slipping into the places locals only whisper about over coffee?

I’ve been hunting for those low‑profile hideaways for years, and every new discovery feels like finding a missing puzzle piece that makes the state’s picture feel whole.

Hiding in plain sight along quiet highways, these ten spots offer experiences you won’t find in typical guidebooks.

Pack your sense of adventure and prepare to explore underground caverns, futuristic architecture, and natural wonders that most Arizonans drive right past without a second glance.

1. Boyce Thompson Arboretum

Driving east on Highway 60 toward Superior, you’ll spot a green oasis that seems impossible in the middle of rocky desert hills.

Boyce Thompson Arboretum sits at 37615 E Arboretum Way, Superior, spreading across 392 acres of trails that wind through collections of desert plants gathered from around the world.

The main loop takes about an hour if you walk at a steady pace, but I always end up pausing near the eucalyptus grove or the hummingbird garden, where tiny birds dart between blooms in blurs of color.

Spring brings wildflowers that carpet the hillsides, while summer monsoons fill the seasonal creeks and make the whole place smell like rain-soaked earth. The Ayer Lake section offers shade and benches where you can sit and watch ducks paddle past reeds and cattails.

I’ve visited in every season, and each time the light hits the saguaros differently, casting long shadows across the paths. The visitor center sells cold drinks and trail maps, though the routes are easy to follow even without one.

Every trip here reminds me that Arizona’s beauty isn’t just about wide-open spaces.

2. Arcosanti

Somewhere between Phoenix and Prescott, a cluster of concrete structures rises from the desert floor like something out of a science fiction movie set in the 1970s.

Arcosanti occupies 13555 S Cross L Road, Mayer, serving as an ongoing experiment in sustainable urban living that architect Paolo Soleri began building in 1970.

The buildings feature rounded arches, sun-tracking windows, and outdoor amphitheaters where students and volunteers still work on construction projects.

I took the guided tour on a Saturday morning, and our guide explained how the design minimizes energy use by stacking living spaces and using natural cooling.

The bronze bells cast in the foundry ring with clear tones when you tap them, and many visitors buy one as a souvenir. You can wander through the café, bakery, and gift shop after the tour, or climb to the upper levels for views across the high desert toward distant mesas.

The whole place feels like stepping into someone’s bold vision of what cities could become if we rethought everything about how we build them. I left with more questions than answers, which felt exactly right.

3. Lava River Cave Trailhead

A hole in the ground opens into one of Arizona’s longest lava tubes, stretching nearly a mile beneath the forest floor.

Lava River Cave Trailhead sits along Forest Road 171B, Flagstaff, where a gravel parking area and information signs mark the start of a short walk to the cave entrance.

The temperature inside stays around 40 degrees year-round, so I wore layers even though it was summer outside, and I brought three flashlights because the cave has zero natural light once you move past the entrance. The ceiling drips in some sections, and the floor can be slippery with ice even in July.

Walking through the tube feels like exploring an alien landscape, with frozen lava flows forming ripples and shelves along the walls. The cave reaches about three-quarters of a mile before the ceiling gets too low to continue comfortably.

I heard water dripping in the distance and saw my breath in the beam of my flashlight. The hike back toward the entrance always feels longer because you’re walking uphill, but the sunlight at the end is worth it.

This is one adventure that makes you appreciate warmth and daylight.

4. Tonto Natural Bridge State Park

Hidden in a canyon near Pine, the world’s largest travertine bridge arches over a creek that runs even in dry months.

Tonto Natural Bridge State Park is located along Nf-583A, Pine, where a narrow road descends into a valley surrounded by ponderosa pines and scrub oak.

The bridge itself spans 183 feet and rises 183 feet above the creek bed, creating a massive stone tunnel that took thousands of years to form. I hiked the Pine Creek Trail down to the base, where water trickles over moss-covered rocks and ferns grow in the constant shade.

The temperature drops noticeably as you approach the bridge, and the sound of water echoes off the stone walls. Several trails offer different viewpoints, including one that takes you across the top of the bridge if you’re comfortable with heights and uneven footing.

The park stays relatively quiet even on weekends because the access road keeps the crowds thin. I spent an hour photographing the light filtering through the arch, watching how the shadows shifted across the stone.

Standing underneath that much rock makes you feel small in the best possible way.

5. Titan Missile Museum

South of Tucson, you can descend into the only publicly accessible Titan II missile silo in the country and stand next to a weapon that once pointed at the Soviet Union.

Titan Missile Museum occupies 1580 W Duval Mine Rd, Green Valley, preserving a piece of Cold War history that feels both fascinating and unsettling.

The guided tour takes you through the control room where two officers would have turned keys simultaneously to launch the missile, then down into the silo where the 103-foot Titan II still stands behind thick glass.

I listened to stories about the crews who lived underground for days at a time, ready to launch within 58 seconds if the order came.

The blast doors weigh 740 tons each and were designed to withstand a nuclear strike on the surface above. You can peek into the crew quarters, see the original equipment, and learn about the accidents that nearly caused disasters during the missile’s operational years.

The whole experience feels like stepping into a thriller movie, except everything here was real and operational until 1987. I left grateful that these weapons stayed in their silos.

6. Colossal Cave Mountain Park

A cave system winds through the Rincon Mountains, hiding rooms and passages that outlaws supposedly used to stash stolen loot in the 1800s.

Colossal Cave Mountain Park is located at 16721 E Old Spanish Trail, Vail, where tours descend into dry limestone caverns that stay at 70 degrees year-round.

The classic tour covers about half a mile of pathways, passing formations with names like the Gila Monster and the Bridal Veil, though the cave contains many more miles of unexplored passages.

I asked the guide about the treasure stories, and she smiled and said people still search but nobody’s found anything yet.

The cave formed millions of years ago when acidic water dissolved the limestone, leaving behind these hollow chambers and connecting tunnels. Unlike many show caves, Colossal Cave is completely dry, so the formations stopped growing thousands of years ago.

The ladder tour offers a more adventurous option, taking you through tighter spaces and requiring some climbing. Above ground, the park has hiking trails, a museum, and a café where you can grab lunch after your underground adventure.

I keep thinking about those hidden passages that still haven’t been mapped.

7. Kartchner Caverns State Park Discovery Center

Near Benson, a cave system remained secret for 14 years while its discoverers worked to get it protected before revealing it to the world.

Kartchner Caverns State Park Discovery Center sits at 2980 AZ-90, Benson, serving as the gateway to one of the most pristine living caves in the United States.

The caverns are still growing, with water dripping from the ceiling to build stalactites and stalagmites that add tiny layers each year. I took the Rotunda/Throne Room tour, which requires reservations because the park limits visitors to protect the delicate formations.

The humidity inside approaches 100 percent, and mist doors seal each section to maintain the cave’s natural environment. The Kubla Khan formation rises 58 feet tall, making it one of the world’s tallest cave columns, and the colors range from white to red to brown depending on the minerals in the water.

Photography isn’t allowed inside to prevent damage from camera flashes, so I just focused on remembering the details. The Discovery Center above ground has excellent exhibits about cave geology and the bats that roost in the Big Room during summer.

This cave makes you understand why the discoverers kept it secret for so long.

8. Queen Mine Tour

You can ride a mining train into the same tunnels where thousands of miners once extracted copper ore from the earth.

Queen Mine Tour starts at 478 Dart Rd, Bisbee, where you’ll put on a hard hat and yellow slicker before boarding the small railcar that carries you 1,500 feet into the mountain.

The temperature drops as you move deeper, and the guide, often a retired miner, explains how the work was done with drills, dynamite, and sheer determination.

I crouched in the narrow passages and tried to imagine spending an entire shift in the darkness, breathing dust and hearing the constant noise of machinery.

The mine operated from 1877 to 1975, producing billions of pounds of copper along with gold, silver, and other metals. You’ll see the original equipment, learn about the different mining techniques, and hear stories about the men who worked here, including the dangers they faced daily.

The tour lasts about 75 minutes, and when you emerge back into daylight, Bisbee’s colorful houses cascade down the hillside below. I gained a new respect for the people who built Arizona’s economy underground.

Some jobs are harder than most of us will ever know.

9. Bowlin’s The Thing

Along Interstate 10, yellow signs for miles in both directions ask the same question: What is The Thing?

Bowlin’s The Thing sits at 2631 Johnson Road, Benson, offering one of the Southwest’s most delightfully bizarre roadside attractions.

You pay a small admission fee and follow a covered walkway through three buildings filled with random collections of oddities, antiques, and peculiar displays that seem to have no connection to each other.

I walked past old cars, vintage torture devices, a replica of a frontier town, and countless other curiosities before finally reaching the main attraction in the last room.

And no, I won’t spoil what The Thing actually is, but I will say that it’s exactly the kind of wonderfully absurd reveal that makes roadside attractions worth stopping for. The gift shop sells shirts, magnets, and other souvenirs that celebrate the mystery.

The whole experience takes maybe 20 minutes, but it’s become one of those Arizona traditions that people either love or roll their eyes at. I fall firmly into the first category because sometimes the journey matters more than the destination.

Plus, now I can finally say I know what The Thing is.

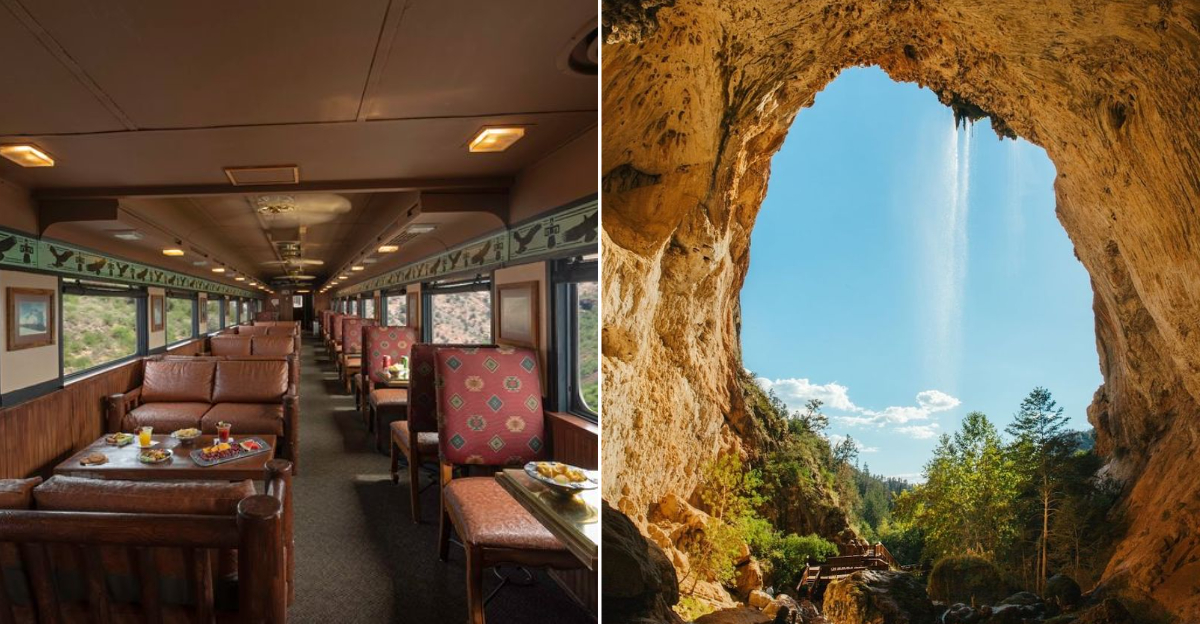

10. Verde Canyon Railroad Depot

This historic railway line carries passengers through a remote canyon that you can’t reach any other way except by hiking or floating the river.

Verde Canyon Railroad Depot is located at 300 N Broadway, Clarkdale, where restored vintage cars depart for a four-hour round trip through 20 miles of stunning desert and riparian scenery.

The train follows the Verde River as it cuts between red rock cliffs, passing ancient Sinagua cliff dwellings, bald eagle nests, and rock formations that glow orange in the afternoon light.

You can rode in the open-air viewing car, feeling the wind and watching hawks circle overhead as the train clickety-clacked along the rails.

The route was originally built in 1912 to serve copper mines, but now it exists purely for the views and the experience of slow travel through wilderness.

First-class tickets get you a private car with comfortable seating and complimentary snacks, while coach offers bench seating and access to the outdoor platforms.

The conductors share history and point out wildlife along the way, and everyone rushes to one side when we spot a heron fishing in the shallows. This is the kind of trip that reminds you why trains used to be the best way to see the country.