This Underground Copper Mine Tour In Michigan Takes You Deep Beneath The Surface

The Keweenaw Peninsula is a place where the earth’s crust seems to have been pulled back like a heavy curtain, revealing a billion years of volcanic history and a century of human grit.

At Quincy Mine, located at 49750 US-41 in Hancock, you aren’t just visiting a museum; you are entering a subterranean cathedral of basalt and copper. Known as “Old Reliable” for its consistent dividends during the mining boom, this site now offers a portal into a world that once rewired the American dream.

In 2026, the allure of the “deep tour” remains one of the most adventurous experiences in the Great Lakes region. You will feel the atmospheric pressure shift, watch the light of the upper world vanish, and stand in the very tunnels that helped fuel the Industrial Revolution.

With a 4.8-star reputation, the site delivers a visceral, tactile encounter with history that stays with you long after you’ve ascended back to the Lake Superior breeze. This hollowed-out mountain of copper offers a chilling, awe-inspiring descent into the dark heart of the American industrial spirit.

To make the most of your journey into the depths, you need to prepare for more than just the view; the temperature underground remains a constant, bracing chill regardless of the summer sun above.

I’ve put together a few essential tips for your visit, from the best footwear for navigating the adits to the specific historical markers on the surface that reveal the true scale of what was once the world’s largest steam hoist.

Start With The Shaft House

The Quincy No. 2 Shaft-Rockhouse looms over the ridge like a skeletal lighthouse, its iron and timber frame silhouetted against the temperamental Keweenaw sky. This is where the earth gave up its treasures. The structure’s intricate chutes and skipways are a masterclass in purposeful geometry, designed to sort, crush, and load copper ore with ruthless efficiency.

It is a hauntingly beautiful monument to a time when Michigan was the copper capital of the world.

Walking through the Rockhouse allows you to trace the vertical journey the ore took, rising from the dark depths before being whisked away toward the smelters. It sets the stage for the human scale of the operation, illustrating the sheer volume of rock that had to be moved to extract a single pound of pure copper.

The Adventurer’s Move: Arrive an hour before your scheduled tour to scout the exterior. The interplay of rusted iron against the green of the peninsula provides a stark, industrial beauty that is a dream for photographers.

Capture the textures of the corrugated metal and the weathered wood, then tuck your gear away. The real adventure begins when you leave the sunlight behind.

Dress For The Underground Chill

The moment you step into the adit, the air changes. It settles at a constant, crisp 43 degrees, a temperature that doesn’t care if it’s a humid 90-degree July afternoon topside. This is a subterranean microclimate where your breath hitches in small, silver clouds and the rocks “sweat” a gentle, mineral-scented moisture.

It feels like a cellar that has spent a hundred years learning the art of patience.

Because the mine is a thermal constant, the “hoodie and shorts” combo favored by summer tourists is a recipe for a very chilly hour. The seasoned visitor knows that the dampness makes the cold feel sharper than a dry winter day.

The Adventurer’s Move: Think in layers. A moisture-wicking base under a durable jacket is the gold standard here. Long pants and closed-toe shoes are non-negotiable, not just for the warmth, but for the uneven, damp terrain of the mine floor.

If you’re the type who feels the bite of the cold early, bring a knit cap. When the guide pauses in the deep tunnels, you’ll want to be focused on the echoes of the past, not the shivering of your own skin.

Ride The Cog Railway Down

There is a mechanical charm to the cog railway that transports you toward the mine’s entrance. As the steel teeth of the rack railway bite into the steep grade, the car clatters gently down the hillside.

It offers fleeting, strobe-like glimpses of Lake Superior through the birch trees before the slope rises up to swallow you. It is a scenic transition that bridges the gap between the modern world and the geological one.

The ride is short, but it serves a vital purpose. It handles the extreme vertical alignment of the Quincy hillside, a practical engineering solution that now provides a bit of theatrical flair to the start of the tour.

The Adventurer’s Move: Secure a spot near the windows for the descent. As the Lake Superior horizon disappears, you can feel the gravity of the hill.

It’s the perfect moment to switch your mindset from “tourist” to “explorer.” Keep your camera ready for that final shot of the sky before you enter the adit. The contrast between the vibrant blue above and the dark basalt ahead is a visual threshold you won’t want to miss.

Meet The Guides Who Animate The Rock

The rock walls of Quincy are silent, but the guides make them speak. Names like Julia, Tim, Sarah, and Ben are frequently praised in dispatches from the mine.

They reflect a culture of storytelling that is both deeply researched and intensely personal. They don’t just recite dates; they weave together the geology of volcanic flows with the gritty reality of labor history, explaining how copper bands were followed through the darkness by men with little more than a hand-drill and a candle.

Keweenaw mining wasn’t just an industry; it was the lifeblood of families and the architect of local schools and towns. The guides treat this social web with immense respect, moving effortlessly between technical explanations of steam power and the poignant stories of the shifts worked in the “death-quiet” of the lower levels.

The Adventurer’s Move: Engage with your guide. Ask about the “Man Engine” or the specific dangers of the 92nd level.

Their knowledge usually goes far deeper than the standard script, and their passion for the “Copper Country” can turn a simple walk through a tunnel into a profound lesson in human endurance. If you find a particular detail intriguing, ask for book recommendations. The mine’s gift shop is a treasure trove of local history that can keep your curiosity burning long after the tour ends.

Listen For Silence, Then Candlelight

At a certain point in the tour, the electric headlamps click off. The darkness that follows is a physical presence, a heavy, velvety weight that makes the ceiling vanish and the walls recede.

You begin to sense the space through your other senses: the drip of water, the sound of your own breathing, the cool draft on your neck. Then, the guide strikes a match, and a single candle flare creates a trembling, golden halo against the basalt.

This demonstration is the emotional heart of the Quincy experience. It strips away modern technology to show you how a miner measured his world.

In that flickering light, the tunnel feels both intimate and terrifyingly vast.

The Adventurer’s Move: Don’t fight the dark. Resist the urge to pull out your phone or turn on a flashlight.

Let your eyes struggle and then adjust. This is the closest you will ever come to the sensory reality of a 19th-century copper miner. In that silence, the “spirit” of the mine is most accessible. It is a moment of profound respect. Treat it as such, and the memory of that single candle will be the most vivid souvenir you carry back to the surface.

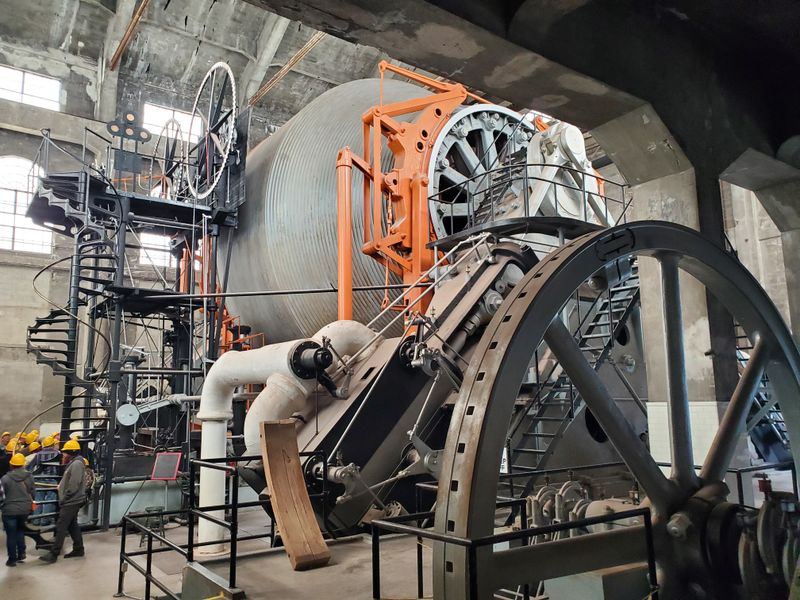

Hoist House: Muscle And Math

If the mine is the heart, the Hoist House is the brain. This “engineering cathedral” houses the world’s largest steam hoist, a gleaming behemoth of drums, cables, and brass gauges.

The sheer scale of the Nordberg Hoist is overwhelming, but the true magic is in the math. This machine was tuned to move tons of rock at high speeds with a precision measured in inches, all while coordinating safety across a vertical system that plunged thousands of feet into the earth.

The room hums with the phantom torque of a bygone era. It is a place where you can see the exact moment when human muscle was replaced by the massive, calculated power of steam and steel.

The Adventurer’s Move: Step back to get a sense of the hoist’s true proportion. It’s difficult to fit the whole machine in a single frame without a wide-angle lens.

Pay close attention to the indicator dials. They show how the hoist operator could “see” where the skips were in the darkness of the shaft, miles away. Ask your guide about the communication system between the hoist man and the miners. It was a life-and-death game of signals and trust that kept the mine running.

Grounds And Ruins Worth Your Footsteps

The adventure doesn’t end when you leave the tunnel. The hillside around Quincy is a sprawling, open-air archive of stone foundations, weathered brick, and rusted rail fragments.

These ruins are the “shadow” of the industrial giant, mapping out where the stamp mills once hammered and where the community of miners lived. The light of Lake Superior plays across these skeletons of industry, making them feel contemplative rather than abandoned.

Wandering the grounds allows you to see the “stamp mill” remnants and the footprint of the various support buildings that made the Quincy Mine a self-sufficient city on a hill.

The Adventurer’s Move: Plan to spend at least 45 minutes exploring the ruins after your tour. Wear sturdy shoes, as the ground is uneven and filled with the debris of a century of work.

Follow the old rail lines and look for the spots where the rock was loaded onto trains. The view from the top of the hill, looking down toward the Portage Lake Lift Bridge, is one of the best in the Keweenaw. It provides a perfect visual link between the mine and the port town that grew because of it.

History In The Rock Itself

The walls of the Quincy Mine are a billion-year-old diary. The basalt carries seams of “native copper,” copper that is 99% pure in its natural state, appearing as bright, metallic punctuation where the rock has been freshly cut.

You can see the dark, volcanic flows and the amygdaloid pockets where the copper was deposited by ancient hydrothermal fluids. The smell is a unique blend of wet earth and old coins.

This isn’t a sanitized museum experience. The rock is raw and immediate. You can see the drill marks and the scars left by the explosives that tore this labyrinth out of the earth.

The Adventurer’s Move: Keep your eyes on the walls, not just the path. Look for the “vugs” or small cavities where minerals have crystallized over millennia.

Listen for the “tic-tic” of water dripping from an overhead vein, the mine’s natural drainage system. Ask your guide about the depth of the mine relative to Lake Superior. Knowing that the system descends far below the lake’s bottom adds a layer of geological vertigo that makes the tunnel feel even more significant.

Logistics That Smooth The Day

Navigating a trip to the Keweenaw requires a bit of foresight. Quincy Mine operates from 10 AM to 4 PM daily during the season, and because it is one of the most popular sites in the region, tours frequently sell out.

The gift shop is a highlight in itself, stocking everything from local copper specimens to deep-dive books on Michigan geology.

Online reservations are the only way to guarantee your spot in the tunnels. The staff is famously efficient, but they work within firm time windows to keep the cog railway and the underground groups moving safely.

The Adventurer’s Move: Book your tickets at least a few days in advance, especially if you’re visiting during the peak summer or the vibrant fall color season.

Arrive at least 30 minutes before your time slot to handle the check-in process. If you have mobility concerns, call ahead. The mine uses a tractor-pulled wagon for the underground portion, and they can provide the most current info on accessibility for that day’s specific route. Being prepared means you can spend your time absorbed in the history rather than worrying about the clock.

Respect The Scale You Cannot See

The most humbling part of the Quincy experience is looking at the mine maps. They reveal a staggering honeycomb of tunnels that plunge nearly 10,000 feet along the dip of the copper vein.

The levels are stacked like notes on a musical staff, extending far deeper than the human mind can easily grasp. The tour explores only a tiny fraction of the upper levels. The rest is now claimed by the rising waters of the deep earth.

This limitation doesn’t diminish the experience. It focuses it. It forces you to realize that you are standing on the very “skin” of a system that was vast, dangerous, and incredibly complex.

The Adventurer’s Move: Spend time at the large map displayed in the adit. Trace the lines and try to project them downward in your mind.

Ask about the “pumping” history, how they kept millions of gallons of water out of the mine for decades. When you walk back toward the light at the end of the tour, do so slowly. The transition from the massive, dark scale of the lower levels to the bright, open sky of the Keweenaw is a “coming up for air” moment that perfectly punctuates the adventure.